Daylight provides many advantages, such as increased productivity and better sleep. Schools consider these advantages when integrating daylight into classrooms to help students excel in their studies.

Classrooms with copious amounts of daylight, however, can be detrimental to students and their performance. Two main causes of concern include glare and increased difficulty for students to read their notes (or notes written on marker boards), experts say.

Read Murrye Bernard’s piece below to learn how some schools are controlling daylight in classrooms — and why window size is so important when designing a facility.

Editor’s note: This piece originally appeared on ArchitectMagazine.com. You can also read the piece here.

Though designers might view larger window areas as more desirable in classroom settings, the ability to control the incoming daylight also has a significant impact on user experience.

Daylight that is not properly managed can cause glare on boards and screens in classrooms.

(Image: David Fuentes Prieto)

The appropriate use of daylight in educational environments has myriad benefits: healthier students and fewer sick days, as well as improved moods, learning aptitudes, and attention spans. In the study “Daylight and School Performance in European Schoolchildren,” published in December 2020, researchers found that “classroom characteristics associated with daylighting do significantly impact the performance of the school children and may account for more than 20% of the variation between performance test scores” in math and logic. The window-to-floor area ratio in classrooms seemed to have the most significant effect, with larger window areas being more desirable.

However, the study emphasized the importance of controlling the amount of incoming daylight, through window shades for example. Stantec has reached similar conclusions through its studies. Since 2012, the global firm’s Research + Benchmarking group has conducted post-occupancy studies in Texas schools designed by itself as well as by other firms. The feedback it has received includes, perhaps surprisingly, dissatisfaction with daylight.

Shivani Langer, AIA, a principal, senior project architect, and regional sustainability leader based in Stantec’s Austin, Texas, office, expounded on these findings in her 2019 article “Education design: How much daylight is right for today’s tech-enabled schools?” Two of the 10 schools surveyed had wall-to-wall glazing, but Stantec’s research group found that even with sunshades and light shelves, user satisfaction with the daylight was very low—even lower than for the traditional classroom layout with two windows at each corner of the room. “The major source of dissatisfaction was glare and the inability of the students to see notes on the marker board or projections on the screen in their classrooms,” Langer says.

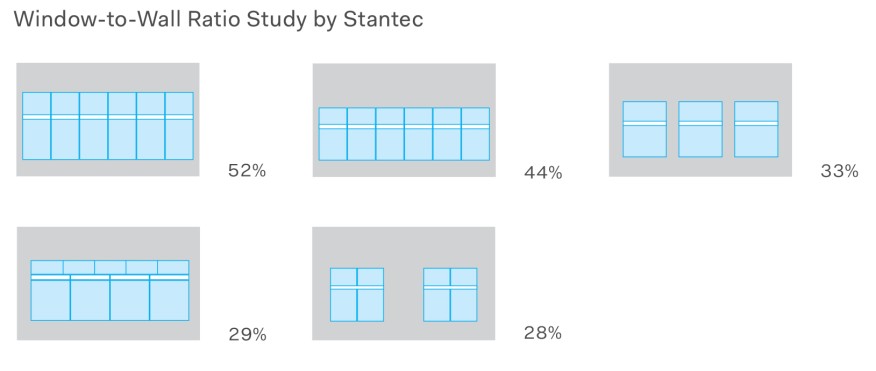

After studying a variety of window sizes and configurations in typical classroom settings in Houston, she and her team discovered that window size is not directly proportional to the amount of useful light available in a space. In fact, the amount of useful daylight illuminance (UDI)—a metric that references when illuminance is supplied by daylight alone—is actually lower in the case of larger windows. “Designing big windows doesn’t necessarily mean adding quality daylight in a space,” Shivani says. “Because glare is not considered useful, the amount of useful daylight available from a space with a 28% window-to-wall ratio may be higher than one with 52%.”

Window-to-wall ratio study by Stantec.

(Image: Stantec)

Successful lighting strategies for educational environments artfully balance daylighting with electric sources and control technologies. From an architectural standpoint, sunshades and light shelves help to mitigate glare. Ample lighting controls, including features such as daylight sensors, color tuning, and dimming, allow for flexibility.

Designers specifying LED sources should aim for a minimum color rendering index of 80 and full-spectrum lamps that promote visual comfort, reduce glare, and exhibit low levels of noise and flicker, which can distract students. Using consistent fixtures throughout the building can ease maintenance.

Here are three projects that demonstrate the controlled use of daylight in educational environments.

Richard J. Lee Elementary School in Plano, Texas, designed by Stantec.

(Image: Stantec)

Richard J. Lee Elementary School

Plano, Texas

Stantec

Lee Elementary School was the first elementary school to achieve net-zero in the state. To dramatically reduce the project’s energy consumption from lighting, the design deploys large windows and daylight harvesting through reflective ceiling tubes, which enable natural light to reach 90% of the interior. “The placement and sizes of windows were strategic to ensure light reaches deep into spaces,” Langer says.

Richard J. Lee Elementary School in Plano, Texas, designed by Stantec

(Image: Stantec)

Richard J. Lee Elementary School in Plano, Texas, designed by Stantec

(Image: Stantec)

Punched openings along the south façade create exterior overhangs for sun shading. Inside, corresponding surrounds further diffuse daylight to avoid glare. With these portals, Stantec has created colorful nooks in which students can read and learn individually.

Nils K. Nelson Bioscience Innovation Building in Hammond, Ind., designed by CannonDesign

(Image: Steve Hall/Hall + Merrick)

Nils K. Nelson Bioscience Innovation Building

Hammond, Ind.

CannonDesign

Housing Purdue University Northwest’s College of Nursing and Department of Biological Sciences, the Nelson Bioscience Innovation Building weaves public spaces and laboratories that showcase teaching and learning innovations. The building is organized around a grand staircase and three-story atrium, through whose glazed walls classrooms and research labs are visible. Exterior windows respond to the interior program, with larger windows allocated to classrooms and labs, and smaller windows to offices. Window sizes are one to three times the width of the modular aluminum composite panels cladding the exterior.

Nils K. Nelson Bioscience Innovation Building in Hammond, Ind., designed by CannonDesign

(Image: Steve Hall/Hall + Merrick)

Nils K. Nelson Bioscience Innovation Building in Hammond, Ind., designed by CannonDesign

(Image: Steve Hall/Hall + Merrick)

“The lighting design follows the lead of the building’s design drivers and centers on concepts of transparency, efficiency, and providing flexibility for future needs,” says Raisa Shigol, a Chicago-based senior lighting designer at CannonDesign. Lighting elements and engineering systems evenly illuminate ceiling surfaces and teaching walls while accounting for spatial geometries and maximizing function and visual comfort.

The labs feature orthogonal arrangements of pendant LED lighting with indirect and direct distribution and flexible control strategies. Linear, angled fixtures convey movement in circulation areas and student hubs. Classrooms and labs feature sunshades to mitigate glare. “Health-education facilities require a unique balance,” Shigol says. “It’s critical to select lighting systems that support a realistic health-care environment and related medical tasks, while also ensuring a facility that nourishes campus and student life.”

Cooke School & Institute in New York, designed by PBDW Architects

(Image: Francis Dzikowski/OTTO)

Cooke School & Institute

New York

PBDW Architects

The Cooke School & Institute is a free-standing building surrounded by green space on three sides—rare for upper Manhattan—and thus has access to an abundance of daylight. The terracotta façade of the school, which serves K–12 students and young adults ages 18–21 with special needs, features a bay window motif, channel glass, and curtain walls. Colored slot windows enable students to identify their own classrooms from the street below. Light passing through these windows creates colored shadows that move across the floor over the course of the day. At the street level, the channel glass provides natural daylight for administrative and classroom spaces while maintaining privacy.

Classrooms are oriented to receive adequate daylight through expansive glazing. “We wanted the natural light to be primary in the learning spaces, supplemented by direct/indirect LED light fixtures,” says project manager Erica Gaswirth, AIA, a New York-based senior associate at PBDW. “In classrooms, the fixtures are divided into multiple daylighting zones, each of which is independently controlled by photo sensors. The lights in each zone are automatically and smoothly dimmed to maintain required light levels for the tasks at hand.”

Cooke School & Institute in New York, designed by PBDW Architects

(Image: Francis Dzikowski/OTTO)

Solar shades, which are manually controlled in classrooms and electronically controlled in the cafeteria, eliminate ultraviolet rays and glare when needed. Linear pendant fixtures in classrooms offer direct and indirect beam distributions, which are individually and manually controlled by wall box dimmers. “The color rendering was fixed to 3000K to complement the architectural spaces as well as to create a uniform color for the entire project,” says Yasamin Shahamiri, a senior associate at the New York-based lighting design firm One Lux Studio, which served as PBDW’s lighting consultant.

Through experience and mock-ups, PBDW has learned to choose fixtures that work in learning environments. The firm also works continuously with the school to troubleshoot any issues that arise. “Many students with special needs have sensory sensitivities as well,” Gaswirth says. “When these children don’t have to expend extra energy tuning out glare, buzzing, or flickering from fixtures—distractions easily ignored by other students—they are able to more fully focus on their schoolwork for longer periods of time.”